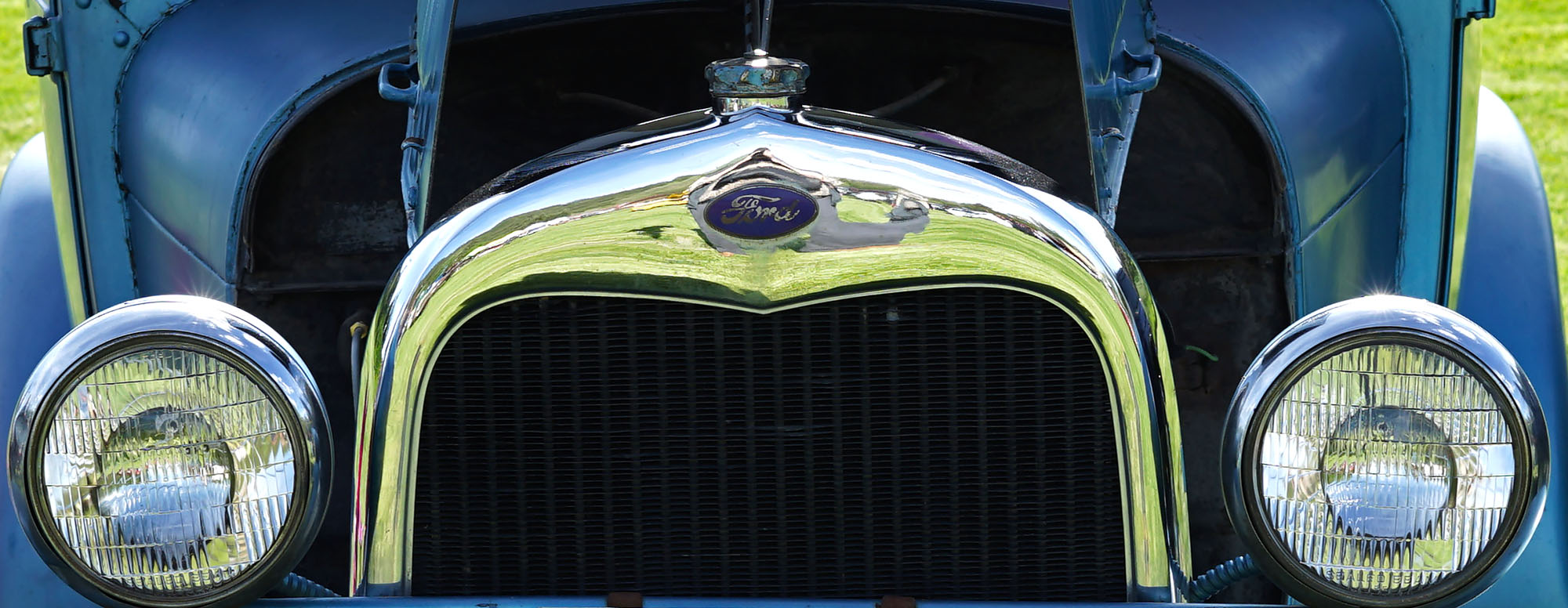

It’s difficult to discuss sharpness without making some assumptions. The photograph itself has to be sharp. That means a good camera and lens, correct focus, steady platform, etc. This discussion assumes that you start with a sharp photograph. And then you print.

As an example, let’s use the Sony A7 II, a 24MP (megapixel) camera, which has a frame of 6000 x 4000 pixels.

Commercial printing (e.g. magazines) is done at 240 dpi. Fine art printing is done at 300 dpi. (Most people can’t see much more than 300 dpi.) At 240 dpi the Sony 24MP camera generates a physical print 25 x 16.7 inches. At 300 dpi the print is 20 x 13.3 inches. (length in pixels ÷ dpi). When you consider viewing distance, however, the further you get away from a photograph, the less dpi you need to create the same illusion of sharpness.

The distance/sharpness is difficult to calculate due to so many variables. But the chart at this website gives you something to go by:

http://resources.printhandbook.com/pages/viewing-distance-dpi.php.

It indicates that at a 24-inch viewing distance, you need 300 dpi to get the maximum sharpness. Yet at a 40-inch distance, you need only 180 dpi to get the maximum sharpness. Think of 24 inches as being about the distance you view a photography book or look at a computer monitor. Think of 40 inches as being about the typical distance you look at a photograph hanging on the wall in a museum, gallery, office, or home.

Using the 40-inch viewing distance, you can generate a 33.3 x 22.2 inch print of a 6000 x 4000 pixel photograph at 180 dpi, and it will look as sharp as can be. But if someone sticks their nose into it (gets closer than 40 inches), it will not look its maximum sharpness.

Another means of determining distance/sharpness is to calculate the maximum viewing distance according to the diagonal measurement of the printed photograph. Some experts say the viewing distance should be 2x, some 1.5x, and some 1x (of the diagonal).

Calculate the diagonal with the formula: c = √(a2 + b2) where a and b are the frame dimensions and c is the frame diagonal. Thus, for a 20 x 13.3 inch print, the diagonal is 24 inches. At the conservative 1x, the viewing distance is 24 inches for maximum sharpness (300 dpi). At 1.5x, the viewing distance is 36 inches. And at 2x the viewing distance is 48 inches. Thus, for these last two distances, you would need only a dpi well under 300 to provide maximum sharpness for viewers.

It’s all very subjective. But one thing is certain. The first consideration of sharpness is how the viewer will see the print. And distance matters.

The next consideration is whether you can improve the sharping because it’s a digital photograph and not a film photograph? For many digital photographs the answer is a modest yes. For some photographs the answer is an absolute yes. Sharping digital photographs is beyond the scope of this article and is also subjective. But you may be able to enlarge a photograph 10%, 20%, or 30% and still retain its inherent sharpness by applying sharping in postprocessing. (However, you can’t take an unsharp photograph and make it sharp with postprocessing.) In other words, just by sharping in postprocessing, you may be able to enlarge a photograph a little without the loss of sharpness.

Another consideration is general enlarging. How much can you enlarge a photograph without noticeably losing sharpness? One of the original guidelines was that you could enlarge about 30% by doing 10% at a time, without noticeably losing sharpness. Today the algorithms are better, but the experts’ opinions are subjective. Some say 50% enlargement. Some as high as 400%. But this is something that depends on the characteristics of the photograph, your enlarging experimentation, and the software you use. You might want to do your experimenting with a small portion of your photograph first before committing to printing the whole enlargement.

You will want to remember that enlarging 2x does not double the frame dimensions. It doubles the area of the photograph. If you double the frame dimensions, you enlarge the area 4x.

Finally, consider the medium. Metal prints can be printed at 300 dpi, although 240 dpi is a typical default for metal printing services. The dpi of inkjet printers is virtually impossible to calculate without a lot of specifications you probably can’t easily get. The dpi for inkjet and laser printers is based on advertising, not on the traditional printing dpi. In other words, a 1200-dpi inkjet printer may print only at 280 dpi according to traditional printing specifications. If you buy a printer, you may want to ascertain the actual traditional print specification first, if available. Likewise, if a photographic service provider uses an ink et printer, you will want to likewise ascertain the actual traditional print specifications.

A word of warning. You can order a 12000 x 8000 print of your 6000 x 4000 pixel photograph, and no one at a photographic service will give it a second thought. They will simply automatically enlarge it 4x as part of their processing. Although they usually have good enlarging software, it raises the question of whether you would rather enlarge it yourself knowing that your photograph will otherwise be automatically enlarged. In other words, just because you can order something, doesn’t mean that it will retain its sharpness to the degree you require for your viewers. You may want to have more control.

What’s my practice? I don’t enlarge anything and don’t worry about sharpness. With my 25 MP camera, this is a practical point of view. Nonetheless, there are always those situations where I need a large print, and enlargement is required. In such cases (rare for me because I print few photographs), I decide how to enlarge based on the factors outlined in this article; that is, I handle each photograph on a custom basis. But if you find yourself enlarging your photographs all the time, you may want to get a camera with more MPs thus enabling you to forgo enlarging so much of the time. The new Sony A7R IV has 61 MPs (35mm type camera) with a 9504 x 6336 pixel frame, and its brand competitors are comparable.

Finally, if you typically crop much of a digital photograph away, you may have a need to enlarge what you have left. In that case, a camera with plenty of MPs is doubly useful to your photography efforts.